ADVERTISEMENT:

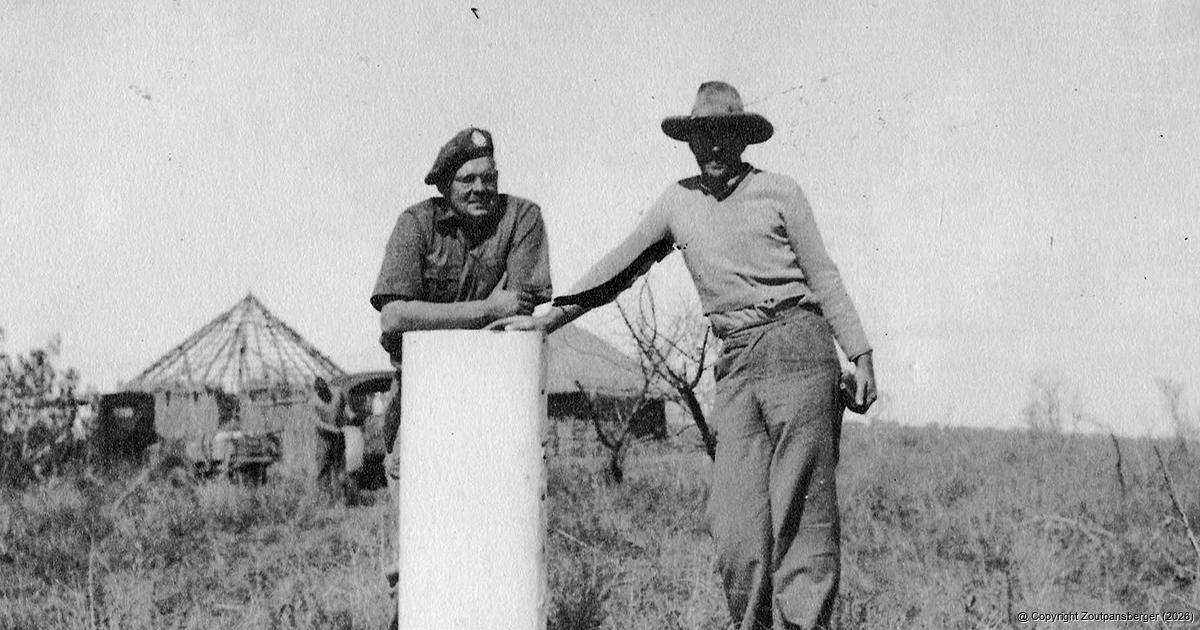

Oom Willem van den Berg (centre), photographed at what may be his farm, with an unknown friend. In the picture he wears his military regalia. He had a passion for the military and was a staunch supporter of the local commando. Earlier in his life, when World War 2 broke out, he was recalled by the Netherlands Army and went for training at Wolverhampton in England. He spent part of the war serving in the Merchant Navy, supporting Allied operations on multiple continents. When he died in 1984, he left some of his belongings and the property to the Moths’ Turbi Hills Shellhole in Louis Trichardt.

Oom Willem not only a traveller, but also a story teller

Date: 26 July 2025 By: Anton van Zyl

For several weeks now, we have been “touring” with Oom Willem van den Berg. Guided by the 16mm film reels he left behind, we have travelled back in time to the places he visited between 1926 and the early 1930s.

Over the next few weeks, we will continue the journey, but this week we pause to find out more about the man himself. Oom Willem was also a prolific storyteller. Fortunately, he shared some of his tales with friends, and these delightful stories were preserved for future generations. This week, we delve into one such story — a glimpse into life on an African farm a century ago.

But first, a brief recap:

Willem van den Berg was born in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, in 1902. He arrived in South Africa in 1926. His first stop was a cattle ranch in the Western Transvaal, where he worked for nine months. He then spent about two years on a farm in the Eastern Free State before settling in the Soutpansberg. He died in 1984.

Among the treasures Oom Willem left behind were film reels dating back to 1926. He also left a collection of stories, some of which were captured in an interview with the late Mr Piet Adendorff, a close friend. These stories were later transcribed by Adendorff’s granddaughters.

One of our favourites is about a certain Dutchman, Hendrik Bosch. Oom Willem first met Bosch in Holland and described him as someone not particularly suited to farm life. Bosch was more interested in anthropology — studying skulls and the history of mankind. “Now, when he mounted a horse, he got up on the one side but fell off the other,” Oom Willem recalled.

Despite this, Bosch was determined to come to Africa. He bought the farm Wintersvlei in the Eastern Free State, near Hoopstad. Oom Willem, at the time, worked for the Van Beek family on a neighbouring farm. Some 16 miles further along, on the upper reaches of the Vetrivier, lived a farmer named Albertus Erasmus, who had four daughters. Old Hendrik fell in love with one of them, Annatjie.

“Every weekend he went there — left on Friday, came back on Tuesday. He bought a motorcar, one of those old Dodges with yellow wheels, and he bought a gramophone. He was very fond of classical music — Mozart and Beethoven, etc. He used to carry this gramophone along when he went ‘om te gaan vry’ (courting) at the Erasmus’s, you see. Of course, she did not know anything about classical music; she only knew Vastrap music and that sort of thing. But all in all, she loved the music. Then, when he was home, he used to write her love letters on beautiful mauve paper. He had a very fine, minute handwriting,” Oom Willem recalled.

“One day I came into the room and he was writing again. I said, ‘Now look, Hendrik, do you really think that girl will read the letters? It’s all in High Dutch.’ ‘Oh no, no,’ he replied, ‘she wants to learn High Dutch. She keeps those letters safe.’”

Oom Willem then recounted the night Hendrik’s courtship came to a dramatic end.

“It was a bright, moonlit night, early on a Saturday morning. In those days, very few people had motorcars — this was 1928. I heard a car coming from far away, getting closer. It entered the yard and stopped in front of the house. Hendrik came in — white as a sheet, with an ugly wound on his head. I asked, ‘Hendrik, what the hell happened now?’ He said, ‘No man, I’ll tell you just now, but please give me a drink.’ So I poured him a good tot of brandy.”

By then, the Van Beeks were also awake, and the four of them sat around the table to hear Hendrik’s tale:

“You know, it is a nice, moonlit night, and the old people went to bed early. We sat on the back stoep, holding hands and a soentjie now and then, and I was playing the gramophone — Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata,” he said.

In those days, toilets weren’t inside the house. Before bed, people would visit the ‘outhouse’ in the backyard — a small building often made of corrugated iron. “Inside was usually an old box with lots of Farmer’s Weekly or Landbouweekblad pages, mostly used as toilet paper — but if you had a long session, also for reading. There was a plank, a bit of candle and half a box of matches, so you had some light for night-time operations,” Oom Willem explained.

Annatjie had gone to her room. Hendrik, whose room was on the back veranda where his car was parked, went to the loo.

With the bright moonlight, Hendrik didn’t need much help finding his way. He lit the candle, opened the door — and suddenly felt as if an ice-cold hand had touched his heart.

Oom Willem explained how he interjected: “Ugh, I know what happened. You found old Albert sitting there, and he knocked you over the head because you came in without knocking.” But Hendrik replied, “No, no! There was no one there.”

“Then what caused the ice-cold hand around your heart?” Oom Willem asked.

“Man, hanging from a string were all my beautiful, mauve love letters. I swung around, and that was when I knocked my head on the door of the outhouse,” came Hendrik’s reply.

Hendrik went to his room and gathered all his belongings — except the gramophone and records, which were in the sitting room. “I couldn’t get them without waking the whole family. They can keep it. They can keep it. But I don’t want to see her ever again,” he said.

“So, Hendrik, what are you going to do now?” Oom Willem asked. “I don’t know,” he said. “But I’ll tell you tomorrow. I’ll think it over tonight.”

At breakfast the next morning, Hendrik announced: “Man, I’m going back to Holland.” Oom Willem asked him what would happen to the farm, the cattle and everything else. “It’s got to be sold. Never mind — I’ll let you know. But I’m going back to Holland as soon as possible,” Hendrik answered.

The following morning, Oom Willem took the old Dodge and drove Hendrik to the station, located on a farm near Bloemhof. For months, nothing was heard from him — until an uncle arrived to arrange the sale of everything.

In the coming weeks, we’ll share more of Oom Willem’s stories. In some, he recounts his visits to the Kruger National Park, back when places like Punda Maria were only just starting to become popular. Keep watching this space.

Viewed: 1911

Anton van Zyl

Anton van Zyl has been with the Zoutpansberger and Limpopo Mirror since 1990. He graduated from the Rand Afrikaans University (now University of Johannesburg) and obtained a BA Communications degree. He is a founder member of the Association of Independent Publishers.

Most Read Articles

Sponsored Content

Recent Headlines